18 Challenges to Administrative Data in Puerto Rico during COVID-19

Daniela Gómez TreviñoResearch Manager

J-PAL North America, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

18.1 Summary

This chapter describes an important stage in an ongoing J-PAL partnership with the Puerto Rico Department of Education (PRDE). Researchers supported the implementation of an online diagnostic assessment test, which took the place of standardized testing of students of grades 3 to 8, and 11 in the subjects of math, English as a second language, and Spanish. In addition to supporting an ongoing randomized evaluation, the assessment offers an opportunity to measure learning loss for future decision-making and research studies. It describes this period of support, the broader relationship, and lessons learned from working with state governments and administrative data. Note that the work to implement the assessment was still in progress as of November 2021, and the descriptions in this case study reflect the current state of an evolving situation. The project received support from the Innovations in Data and Experiments for Action Initiative (IDEA), funded by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, during the COVID-19 pandemic to address the interruption to administrative data collection critical to an ongoing research study.

18.2 Introduction

An important advantage of using administrative data for research is that data is usually already collected and stored for operational purposes. From the researcher’s perspective, this appears to occur automatically, lowering the logistical burden and cost for researchers and participants, ensuring near-universal coverage, and enabling long-term follow-up. However, administrative data collection is not always automatic or guaranteed. This case study describes a randomized evaluation of a management training program for school principals in Puerto Rico, which relies on standardized test scores collected by the Department of Education to measure outcomes for students, principals, and schools. The administration of standardized tests was halted by the COVID-19 pandemic and a resultant shift to remote learning. At the time, J-PAL North America had an ongoing partnership with the PRDE. The response to the interrupted data collection — here, the implementation of an online diagnostic assessment test — was made possible by recognizing shared interests among researchers and education officials. Although (hopefully) a once-in-a-lifetime occurrence, the pandemic response offers lessons for research-practice partnerships where shifting priorities or new crises may require adaptability.

The PRDE is responsible for managing about 845 state-operated schools in Puerto Rico, with 292,518 students and 24,240 teachers, making it one of the largest school districts in the United States by enrollment. In Puerto Rico, 57 percent of children live in poverty and most children have academic outcomes far worse than their peers in the mainland United States even before the COVID-19 pandemic (McFarland et al. 2019) (McFarland et al. 2019).

J-PAL North America has been involved in this research-practice partnership since November 2016, when the PRDE was selected by J-PAL as a State and Local Innovation Initiative partner, with improving education identified as a focus area. J-PAL embedded an evaluation officer in the PRDE to support the researchers and provided short-term research management support that helped launch the following intervention.

To improve management practices in Puerto Rican schools and thereby improve student achievement, the PRDE collaborated with J-PAL affiliated researchers Gustavo Bobonis, Marco Gonzalez-Navarro, Daniela Scur, and Orlando Sotomayor in 2018 to design and implement a randomized evaluation of a system-wide principal leadership management training program called Academia de Desarrollo Profesional de la Educación para la Gestión de Liderazgo y la Profesionalización314 (EDUGESPRO) using administrative data collected by the PRDE.

Each cohort of principals is trained over the course of one academic year (approximately 154 hours in total) through a series of 10 seminars followed by 13 workshops and coaching throughout the academic year. The program targets five managerial levers: educational leadership and strategic long-term planning, instructional data-driven planning and performance tracking, goal and target setting, school culture, and personnel management. The evaluation relies on administrative data collected by the PRDE, including student scores on the standardized test known as Measurement and Evaluation for Education Transformation (META-PR, from its acronym in Spanish).

As the evaluation has progressed, J-PAL and the PRDE have continued to find ways to support and grow this partnership. During the period described in this chapter, this included research management support by J-PAL staff designed to identify opportunities to continue to measure outcomes for the study in light of COVID-19. In practice, this led to J-PAL supporting the implementation by the PRDE of an online diagnostic assessment test for students, to measure learning during remote education.

As part of a set of cases dedicated to the use of administrative data for research, the focus on original data collection may seem an odd fit. Administrative data, however, still must be collected and, as described below, researchers may help contribute to that process. One way of achieving the goal of increasing the use of administrative data for evaluation is through developing stronger institutional partnerships between researchers and data providers and implementing partners such as governments. Supporting the partnership was the primary goal of the research team during this period, and this has already paid dividends in generating new data and launching new studies. Ultimately, the assessment test was the PRDE’s (not researchers’) data collection operation, conducted for its own operational purposes. Questions of administrative data are addressed more fully at the end of this chapter.

This case first describes the randomized evaluation in more detail, how J-PAL staff and affiliated researchers worked with the PRDE during the COVID-19 pandemic, and lessons learned for collaborating with governments and working with administrative data.

18.3 Evaluation of EDUGESPRO

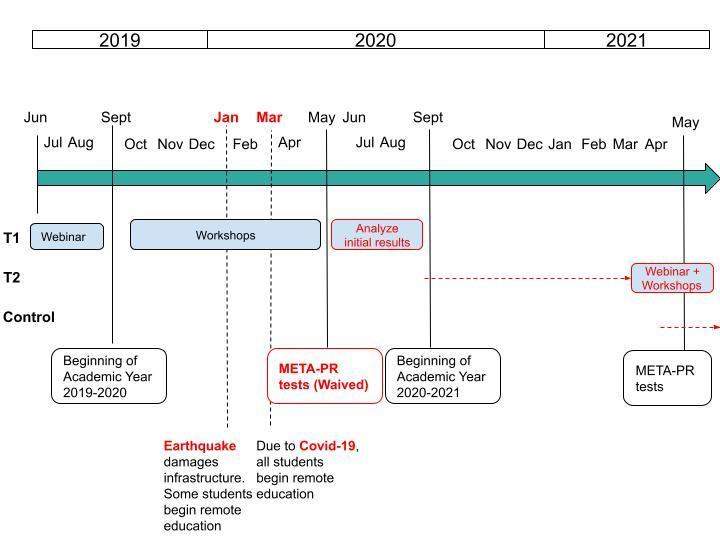

EDUGESPRO’s evaluation is the core collaboration between the group of researchers and the PRDE. To evaluate this program, school principals were randomly assigned to one of three training cohorts to be offered the opportunity to participate in the EDUGESPRO program in the summer of 2019 (T1), 2020 (T2), or 2021 (control). Exploiting the cohort-by-year program design, researchers used a phase-in randomized evaluation, meaning they randomly divided the group of principals in cohorts and provided the training to each cohort one at a time to identify the causal effects of the intensive management training on outcomes of interest. One of the main outcomes of interest was student achievement measured through annual standardized testing. As shown in the following timeline, the interruption of standardized testing in May 2020 caused delays and disruptions to the first analysis of the intervention’s results.

Figure 18.1: Timeline for Evaluation

18.3.1 Data Used for Evaluation

The research team’s intention was to use PRDE data on a broad array of student, principal, and school characteristics as well as outcome data for academic years 2011–2012 through 2021–2022. The data to be used by the research team includes the following:

Student-level measures: test scores in Spanish, math, and English for grades 3 to 8 and 11; test scores in science for grades 4, 8, and 11; transcripts; class schedules; absences; disciplinary incidents; poverty status; and special needs status, among others.

Teacher- and principal-level measures: school and class assignments, attendance, professional history (tenure, educational degrees earned and where, prior assignments in the system).

School level measures: location (coordinates) of the school, grade span, infrastructure, accountability classification, student retention and graduation rates, and closure status.

Researchers executed a data-sharing agreement with the PRDE at the beginning of the EDUGESPRO evaluation to receive this data for the purpose of the study. This agreement went into effect when the implementation of the evaluation started in 2018. The agreement works both as a memorandum of understanding to establish the research-practice partnership and a data-sharing agreement that specifies that the research team can access the Department of Education’s data for research purposes. It also describes data security considerations like the fact that all data is processed and stored in a secure server in the University of Toronto. The researchers also intended to link PRDE administrative data to Development World Management Survey results as they concluded the different stages of the evaluation starting in 2018.

18.3.2 Challenges

In early January 2020, a 6.4 magnitude earthquake hit Puerto Rico, causing infrastructure damage and the temporary closure of many school facilities. On March 16, 2020, the PRDE closed all school facilities and announced that all learning would be remote until further notice due to the COVID-19 pandemic. In response, school districts across the United States, including Puerto Rico, requested and received waivers from the US Department of Education for completing their mandatory annual standardized tests. This waiver led the PRDE to decide not to administer META-PR in May 2020, meaning that there are no records of student performance since, in some cases, before the summer of 2019. The testing waiver was implemented in recognition of the fact that states would not be able to get fair, reliable, and valid assessment results given the abrupt transition to online education (Devos 2020) (Devos 2020).

Amid this challenging scenario, there was also an election for governor in Puerto Rico, leading to personnel changes in the PRDE. This was a challenge because new personnel were hired and had to get up to speed on the department's efforts to gather evidence to inform COVID-19 response policy.

After all schools closed in March 2020, EDUGESPRO’s training program was briefly suspended, but training resumed fully online in April as the program had the potential to support principals during the pandemic.315 The original schedule for the intervention had to be changed, so the webinars and workshop for the second cohort were delayed from September 2020 until April 2021; however, the cohort-by-cohort approach to the intervention is still proceeding in order.

Delaying standardized testing due to COVID-19 posed a significant challenge for the study because the ability to draw causal comparisons between cohorts exists only when some cohorts have yet to receive the treatment. Moving outcome measurements to a later date while the intervention is ongoing limits the comparisons that can be drawn. The lack of META-PR at the end of the 2019–2020 school year meant there was no opportunity to measure student gains after the first cohort of principals received management training. After assessing whether grades could be used, the research team concluded that the variation between schools, classes, and grades would challenge the validity of any comparisons.

Measuring student achievement was not the priority in a world looking to adapt to the new COVID-19 reality. Given what was known about COVID-19 in March 2020, the priority was to contain the spread of the disease by continuing school closures and avoiding the type of enclosed settings traditionally used for in-person testing. However, a side effect of this policy change was that ongoing research projects that required standardized test score results were in jeopardy.

18.4 Identifying Solutions to Data Disruptions

Even amid these critical short-term priorities, the PRDE, particularly its Assessment Unit, knew that the lack of tests was going to impact the way they think about education policy. They were committed to developing an alternative that would allow them to understand the needs of the students across the island to address them during and after the pandemic. The solution was to implement an abridged version of the META-PR test online as a diagnostic, low-stakes (i.e., not tied to grades or graduation) assessment. The resulting data will provide insight into students' specific education needs and could also be useful for current and future research.

To help implement the assessment, the Assessment Unit leveraged its relationship with the research team and the shared interest in producing data that could be used in lieu of standardized tests. In turn, J-PAL-affiliated researchers and staff saw providing technical support to the PRDE as an opportunity to strengthen and expand the research-practice partnership in Puerto Rico.

18.4.1 Why Was the Research Team a Trusted Partner?

Over the course of the EDUGESPRO evaluation, the research team demonstrated that they shared common goals with the PRDE of improving learning outcomes, reducing inequality in student academic achievement, and providing high-impact professional development tools to the PRDE’s leaders.316 The EDUGESPRO evaluation was an active research project involving close collaboration between researchers and the PRDE both when the earthquakes hit the island and when schools closed in response to COVID-19. Additionally, the project included an embedded evaluation officer who works within the PRDE and closely with the operations manager of the department’s Institute for Professional Development. This timing and close ties made the research team and the PRDE natural allies in finding alternatives to the lack of standardized testing. Soon the research team, in collaboration with research staff from J-PAL, started directly supporting the PRDE’s Assessment Unit, holding standing meetings to discuss options to implement a test that students could complete from their homes in the summer of 2020.

18.4.2 Implementation Support

Our team joined an ad hoc working group that included the Assessment Unit and the third-party testing provider. While the PRDE and the test provider designed the test and online infrastructure, trained administrators on how to use the system, dealt with technical issues, and communicated plans to roll out the test to schools and families, researchers provided assistance on several particular challenges.

One challenge was that tests had never been administered remotely. Here, the research team supported the Assessment Unit by working on a schedule to implement the test and suggested that they first implement a pilot for grades 2 and 9 (grades that are not normally tested with the META-PR test) to refine the approach and to be able to manage any questions from school officials.

A second challenge was that many schools were not used to implementing an online version of the test, although some had experience administering the META-PR in computer labs rather than in paper form. Here, the research team suggested pairing principals experienced in online testing with other principals for support.

A third challenge was that given that the test would not be tied to grades or graduation requirements, the research team anticipated low take-up. For this reason, it also offered to monitor the test’s progression by analyzing participation rates while the test was being implemented. Researchers developed automated reporting to principals after the testing period with information on the percentage of English, math, Spanish, and natural sciences sessions started or completed in their schools. In addressing each of these challenges, the research team made use of techniques similar to those used in managing the rollout of a randomized evaluation.

18.4.3 Results

The PRDE completed a pilot of the diagnostic assessment in April 2021 and plans to complete the full assessment by the end of October 2021. Implementation happened slower than expected as ever-evolving pandemic regulations and public health considerations shifted the testing timeline on multiple occasions. In addition, legal and contractual obligations with the test provider needed to be addressed before implementation. Implementing the test occurred against a backdrop of leadership changes due to the election, bandwidth constraints in the Assessment Unit, and a pandemic, during which standardized testing was not a top priority. In these circumstances, researchers were able to provide additional bandwidth—such as creating plans for implementation in light of the pilot’s results—while being sensitive to established processes that specified how this type of test could be created and implemented.

While the assessment process is still ongoing, the EDUGESPRO study is not over yet. Being flexible and supportive of the PRDE has helped deepen the relationship between the PRDE, J-PAL, and the researchers. The mutual trust needed to collaborate on research has been strengthened through time spent cooperating on this challenge, which has opened additional opportunities to do research. For example, Gustavo Bobonis and Orlando Sotomayor, joined by Philip Oreopoulos and Román Andres Zárate, have begun an evaluation with the PRDE of computer-assisted learning to combat learning loss due to COVID-19. Bobonis and Sotomayor connected with another agency, the Puerto Rico Department of Economic Development and Commerce, which is now working with J-PAL, through the State and Local Innovation Initiative, to develop an evaluation of training in case management and soft skills for their workforce development staff. J-PAL, the research team, and the PRDE are also exploring ways to formalize an institutional partnership. Finally, J-PAL staff continue to be involved in conversations on data governance and making data accessible and usable for research with the PRDE. These conversations are in early stages but hope to build on the work of the EDUGESPRO evaluation, the diagnostic test implementation, and the department’s existing data-sharing infrastructure.

18.4.4 Is This Administrative Data?

This case blurs the line between primary and secondary data collection. On the one hand, this was a process to collect data for the PRDE’s operational purposes, based on the approach used in the existing collection of META-PR standardized test data. On the other hand, the research team was involved in the data collection process, with usefulness for the evaluation of EDUGESPRO top of mind. Ultimately, what the research team offered was support through the challenges posed by the circumstances, and there was no additional data collection that would specifically serve the purposes of their evaluation. Throughout the whole process, the PRDE was always in charge of implementation and changed plans as necessary as it navigated the bigger picture and balanced educational needs and health and safety protocols. As a result, many of the research team’s suggestions did not end up being implemented, such as the original testing schedule or a platform for troubleshooting testing issues.

Nonetheless, this case is an important reminder that administrative data still often must be actively collected before it can be used for evaluation and research. Researchers familiar with data collection of their own, as well as with the implementation of complex research, can contribute to these efforts. Improving state data capacity is often necessary for the delivery of an intervention as well as the measurement of its effects. Researchers may have opportunities to consult on data capacity building, even in more typical circumstances.

18.5 Conclusions

18.5.1 Benefits of the Diagnostic Test to Puerto Rico

The COVID-19 pandemic was not the first disruption of in-person learning for students in Puerto Rico. The island’s location makes it vulnerable to hurricanes, earthquakes, and other natural disasters that have the potential to disrupt education. Having a plan in place to develop and implement an online test adds value beyond simply finding an alternative to testing during a pandemic. The data collected during the diagnostic test holds the possibility of better targeting student needs on the island and quantifying learning loss. Additional research could also use this data as a baseline to understand what efforts are effective at improving student performance after the COVID-19 pandemic. The PRDE is now better equipped to respond to new requirements from the federal government, issued February 22, 2021, that school districts find ways to administer standardized tests in 2021.

18.5.2 Considerations for Working with Governments to Implement Administrative Data Collection

Despite the one-off nature of the collaboration, some lessons emerge that may be useful given the opportunity to consult on administrative data collection.

Flexibility in the research-practice partnership, while maintaining focus on the common goal, proved to be key. Both the research team and the Assessment Unit went well above their original agreements to set up the infrastructure for this test. The disposition of researchers and government officials was the basis for thinking about an alternative to standardized testing. The process took months, several reviews from the legal team, and multiple iterations to address implementation details, but having in mind the common goal of understanding students’ needs was at the core of the strategy.

Iterating through every step of the process multiple times should be expected. Flexibility is required here. Importantly, this can be a helpful process as there are always new implementation details to address and going through the whole process multiple times can support the implementing partner in thinking about all possible scenarios.

Identify constraints early. The research team was able to provide support thanks to the guidance of the Assessment Unit, who expressly mentioned its constraints and flagged the activities in which it needed support the most. The research team was able to provide additional capacity that the PRDE did not have. For example, it could attend meetings and start thinking about implementation details without needing to go through an administrative approval process. It has also been able to help the PRDE think through challenges generally. At the same time, it was able to provide researcher-specific skills like additional analysis that can improve data collection.

From the implementing partner’s side, it was important to communicate clearly about the legal steps needed to introduce a new process to collect data. This process took months and required the PRDE’s legal team to review the contract with the testing provider several times before approval. Additionally, it was necessary to clarify the limitations within their purview. For example, the Assessment Unit clarified at the beginning that it could not make the test mandatory or assign any grade value to it as homework. This was key when thinking about the test’s implementation since it has implications for researchers who should consider power and selection bias when assessing the coverage of the data for research purposes.

The support of the embedded evaluation officer was fundamental. Emily Goldman, evaluation officer, was a key part in coordinating efforts between the research team and the PRDE. Her position gave her both flexibility and legitimacy to work on planning the implementation of the diagnostic test while considering the research team’s needs. Goldman’s position existed for the purposes of the EDUGESPRO evaluation, but she has been able to expand her support to the PRDE more generally. Researchers may consider embedding staff on site either for specific research projects or for building data capacity.317

18.6 Questions

In the following, we respond to the type of questions that relate the framing and structure of this project to the format of the Handbook. The questions can be taken to guide researchers in how to address the various points discussed throughout this Handbook.

18.6.1 Institutional setup

Who are the parties to the data access mechanism in this case study? Is the data provider also the data custodian/data host, or has a third party (data intermediary) taken on this role?

The parties to the data access mechanism are the PRDE and, in our case, the University of Toronto (the researchers’ institution). The data warehouse is maintained by the PRDE, with the help of a contracted data services company. Some data is initially collected by third-party service providers like education testing companies, but these parties are not parties to the research data access mechanism. All data used for research is transferred by the PRDE to the research institution.

18.6.2 Legal context for data use

Are there any legal restrictions on who can be given access to the data? How were those legal restrictions satisfied (memorandums of understanding, data use agreements, etc.)?

All student records from elementary to postsecondary school are protected by the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act (FERPA). Typically, FERPA requires individual consent from students and/or their guardians to release records. FERPA restrictions would not apply to teacher, principal, or school level records. The PRDE’s Manual de Gobernanza de Datos (Data Governance Manual) (Puerto Rico Departamento de Educación 2016) specifies which individuals or entities oversee data protection and privacy as well as the guidelines and best practices to comply with FERPA. The PRDE executes data-sharing agreements following procedures detailed in the Data Governance Manual and all these agreements follow FERPA principles. In the case of this study, researchers obtained consent for use of student records.

- Have any memorandums of understanding, data use agreements, etc. been generalized, or are they still specific to this partnership? What guidance could you give to the next party wanting to negotiate a memorandum of understanding or data use agreement with the same data provider?

The PRDE has an established process by which researchers may request data from the department, which is detailed in the Data Governance Manual. The appendices in the manual contain a data request form, confidentiality and data disclosure agreements, and a data destruction form that must be completed at the end of a project. Each party requesting data will need to execute an agreement customized to its data request.

For the EDUGESPRO study and the broader research-practice partnership, the PRDE and the University of Toronto first executed a data-sharing agreement in 2018. A University of Toronto template was used rather than the PRDE template, but the agreements contain all of the elements that the PRDE requires. When executing data-sharing agreements, J-PAL recommends starting with a template that at least one party is already comfortable with.

The 2018 agreement has served as a master data-sharing agreement for the partnership, with the appendices containing study-specific research descriptions and data requests (years of data, variables, and any specifics of data linkages and transfers). The 2018 agreement contains an appendix for the EDUGESPRO evaluation, and a second appendix was added in 2021 for the computer-assisted learning evaluation. This particular arrangement may not be generalizable and owes to the fact that the institutions that are party to the agreements have not changed and the investigator teams and data needs for each study are broadly similar. Other researchers should generally expect to execute complete and unique agreements for each research study or data request they undertake. However, it is likely that subsequent data requests from the same data provider may proceed more quickly once an initial relationship has been established.

18.6.3 Making data usable for research

Have the partners completed the process of making the data usable for research? If not, is it taking longer than expected or is it on track? What obstacles were encountered and how were they addressed? Who is handling this part: the data provider, the researcher team, or a joint working group?

Data from the diagnostic test is not yet available since the test has not been fully administered. However, as with the information collected from the META-PR tests, once the data on student performance is collected, it will be processed by the PRDE and added to the centralized, cloud-based data warehouse. The information will then become available to researchers who have established a data-sharing arrangement with the department.

Based on previous transfers of administrative data early in the project, it appears that data is transferred in quite raw form. Researchers should plan significant time for validating, cleaning, and wrangling the data into usable form. Researchers should also take care to ensure that the data has been sufficiently de-identified before analysis.

The following questions will explore how you are planning to protect the information of the people and business in the data and to frame allowable research (rough alignment with the “Five Safes” principles).

18.6.4 Expanding access

Are you planning, or is your project considering, to expand access to other researchers? If yes, how do you plan to select projects, researchers, and institutions that will be granted (secure) access? If not, then please discuss what you feel are the constraints to doing so in this case. (Relates to safe people/safe projects and touches on safe outputs; also legal context for data use.)

Researchers can request access to the PRDE data by completing a Request for Statistical Data as shown in Appendix A (pp. 52–53) of the Data Governance Manual. The request should specify what data is requested, what level of data researchers will use (e.g., student or school level), and the reason for the request. Data at the student level can only be released if the researcher completes a data confidentiality agreement and a data disclosure agreement. After study completion, researchers will also need to fill out a guarantee form of data and confidential information destruction. The request form is not specific to research and is designed to accommodate requests from parents, media, or other members of the community as well. Researchers should also have obtained their institution’s institutional review board approval if conducting human subject research.

Because it was part of the original pilot data access, and as trusted partners, the J-PAL-based research team continues to be involved in ongoing discussions related to data governance. However, all data access is controlled by the PRDE.

18.6.5 Technical setup

Are you planning to require access through particular technical means (remote access, designated secure computers, computer security plan), and/or particular legal means (enforceable laws or contracts/data use agreements under local law)? (Relates to safe settings but also legal framework for granting data access.)

The generic memorandum of understanding/data use agreement adapted for this partnership indicates that the PRDE will transfer data to researchers through a secure file transfer protocol, an encrypted cloud-based solution, or an encrypted hard drive. All the data retrieved from the data warehouse must be stored and analyzed through a secure server, and it cannot leave the hosting institution’s premises. In the case of this project, that server is located at the University of Toronto. This means that no data is available on researcher laptops, and all access is remote, using Windows- or Linux-based access methods. Additionally, each authorized user must be assigned a unique username and password to access the data.

18.6.6 De-identification and similar

If you are currently working with detailed confidential data, will others in the future be able to access the same data, or will accessible data be modified to provide “safe” access in compliance with local privacy and data use laws? Examples of such modifications include (but are not limited to) redacting, de-identifying, or aggregating the data for ethical and data security reasons before sharing.

Researchers are working with de-identified, individual-level data, which cannot be shared beyond the project team. Any published results or data must be aggregated to cell sizes of at least five individuals to maintain confidentiality of potentially re-identifiable subgroups. Other researchers would need to request individual-level data directly from the department, following the relevant data access procedures addressed above.

18.6.7 Data life cycle and replicability

Have you given thought to the preservation of data used and generated by this project, the future reproducibility of derivative data products (including protected data), and the research that used such data? Could future researchers recover data that you are currently using? (Relates to data life cycle and replicability.)

The ad hoc diagnostic test was only intended to be implemented once; however, because the results will be integrated in the central data warehouse, researchers other than those currently working on the assessment’s implementation will be able to access this data in the future. This data will be crucial to measuring learning loss during the disruption caused by the world pandemic. Data held by the research team must be destroyed at the conclusion of the research project, but the original data will be held in the data warehouse for an indeterminate length of time. This information is not currently in the governance manual.

18.6.8 Sustainability and continued success

Have you given thought to the sustainability of the effort, both financial sustainability (covering costs of making data accessible in the long run) and institutional buy-in (satisfying legal and societal expectations of benefits)? (Relates to sustainability and continued success.)

Currently, there is no cost associated with acquiring PRDE data; however, the PRDE has a limited ability to clean and harmonize data, link data sets, or produce analysis.

Thinking more broadly about sustainability, as noted in the case, the research team and the department have invested significant time and effort in capacity building and in conducting collaborative research. These efforts and costs are not well accounted for when thinking only about the data access mechanism. In particular, embedding staff in the department (who have direct access to the data warehouse) has been essential to the smooth conduct of the study, and similar approaches (and related costs) should be considered when conducting future research.

To ensure sustainability and continued success, researchers should approach collaboration with the department from the perspective of shared objectives, such as improving education on the island and improving evidence-based decision-making, such that data relationships continue to be mutually beneficial.

References

Bobonis, Gustavo, and Nicolas Riveros Medelis. 2019. “Policymakers and Researchers Collaborate to Improve Education Quality in Puerto Rico.” J-PAL Blog. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/blog/7-9-19/policymakers-and-researchers-collaborate-improve-education-quality-puerto-rico.

Devos, Betsy. 2020. “Dear Chief State School Officer.” US Department of Education. https://www2.ed.gov/policy/gen/guid/secletter/200320.html.

McFarland, Joel, Bill Hussar, Jijun Zhang, Xiaolei Wang, Ke Wang, Sarah Hein, Melissa Diliberti, Emily F. Cataldi, Farah B. Mann, and Amy Barmer. 2019. “The Condition of Education 2019.” Publication NCES 2019144. National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.Asp?Pubid=2019144.

Puerto Rico Departamento de Educación. 2016. “Manual de Gobernanza de Datos Del Departamento de Educación Del Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico.” Version noviembre 2017. Estado Libre Asociado de Puerto Rico. https://www.de.pr.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Manual_de_Gobernanza_de_Datos_-en_proceso_para_revisin_-5.pdf.

Sachsse, Clare. n.d. “Real-Time Monitoring and Response Plans: Creating Procedures.” J-PAL Research Resources. Accessed July 11, 2022. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/resource/real-time-monitoring-and-response-plans-creating-procedures.

Varela Vélez, Damarys, Emily Goldman, and Gustavo Bobonis. 2021. “Pursuing Evidence-Based Policymaking During Crisis.” J-PAL Blog. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/blog/3-23-21/pursuing-evidence-based-policymaking-during-crisis.

In English, Education Professional Development for Leadership and Professionalization Management Academy.↩︎

Varela Vélez, Goldman, and Bobonis (2021) document in more detail how the program has shifted to respond to the crisis.↩︎

Bobonis and Riveros Medelis (2019) document how policymakers and researchers collaborated to improve education quality in Puerto Rico.↩︎